My daughter’s pet ball python, Smeagol, died over the weekend. We had no reason to think anything was wrong with him. The last time I observed him for any length of time—Friday, as I was yawning through the long pauses of eliminating a computer virus—he seemed just fine, climbing the ceramic branch/rock fixture in his cage. Sometime between then and Sunday, he vomited up his last meal—a partially-digested black mouse, eaten several days before—and shuffled off this mortal coil, while coiled on the floor of his cage. I first took notice because he was lying there with his “nose” up under his body, which would have made it extremely difficult for him to breathe—had he still been breathing.

Smeagol was only about ten years old—not all that old for a ball python. And he wasn’t around long enough for me to resolve my mixed feelings about him. To put it mildly, I am not a big fan of snakes. To put it less mildly, they freak me the f*ck out. Constrictors, like Smeagol, don’t raise a panic in me as bad as smaller, squigglier snakes, or, of course, vipers and the like that can cause all manner of swelling, necrosis and more complete death with a single bite. But, still, he was a snake. And for me, that took a lot of getting used to—or not getting used to.

When my wife questioned my dislike of snakes, and more specifically, my queasiness toward our daughter’s pet, I told her that snakes are essentially tubes that crap out of one end, and bite with the other, and that being shat on and bit are not high on my list of favorite things. I didn’t explain to her how, when I saw a snake just out and about, say, in a field or a forest, I would completely lose my mind. She’s only come close to witnessing a subdued version of that once or twice. She still tried to convince me that Smeagol was cute—and he was as far as snakes go. He was pretty, even, with a funky black and brown pattern, a white underbelly, and a face that looked to be smiling.

We had invited him into our home under the thought of good parents supporting our child’s interests. Back when she was in the fourth grade or so, our daughter got caught up in the idea of having a pet python. I told her if she could save up the money for a snake, I would buy the cage—a large, glass tank, with a screened, slide-out lid—for her birthday. Truth be told, I wasn’t sure she would meet the challenge. Ball pythons are not cheap; and I figured something else would capture her attention before she finished piecing together the money. But cash received as birthday gifts put her over the top of her fundraising goal, and she held me to my promise.

On the night we first brought him home, Smeagol bit my daughter, who admittedly was not exercising any caution whatsoever toward a small, confused animal who had just been stuffed into a box and transported through a cold, November night, to his new and unfamiliar home. I tried to tell her to just put the box in the cage and open it there, to let him come out in his own time. But instead, she set the box on a table, flipped it open, and reached in. Chomp!

Granted, when Smeagol bit anybody, it was more like a nip, designed as a quick warning. But he invariably drew blood with his little, hooked teeth when he did it. It was lightning fast, too, almost impossible to escape once he had a mind to do it. I know of two occasions, aside from his first few minutes in our home, when Smeagol bit my daughter. I also remember him taking a shot at one of our dog’s noses. The dog was just curious and unsure what to make of Smeagol. Smeagol took the dog’s face, with its looming mouth, to be a threat. Both dogs steered clear of him after that—she because she’d been bitten, he because I like to believe he shared my general belief in the benefits of snake avoidance.

Although it’s not good to speak ill of the dead, at times I wondered if Smeagol was perhaps something of a jerk among pythons. But then I figured he had, on average, only committed about one quick bite every two years—not bad considering everything he was put through, including visits to my daughters’ classrooms, and my wife’s classrooms, where he behaved around preschoolers and grade schoolers, even when one or two of them made lunging grabs at his face.

Personally, I never got bit by Smeagol, most likely because I kept my distance, even though, with my daughter spending less and less time at home, it fell to me to take care of most of his feedings and cage cleanings. My wife was the main one to spend time “playing” with Smeagol–letting him roam outside of his cage or drape himself over her shoulders. But, sometime in the last year, he bit my wife as she tried to retrieve him from behind a huge bulletin board that was leaning against a wall. Prior to the wife-biting incident, I had a theory that Smeagol’s likelihood of biting someone was, like with German Shepherds, tied to some sort of fear-sensing mechanism. With that one bite, my theory went out the window, as I knew my wife was the only one who had always approached Smeagol with a complete lack of fear, and a full sense of trust and love. This one bite sharply reduced my wife’s willingness to provide Smeagol with passes outside of his cage.

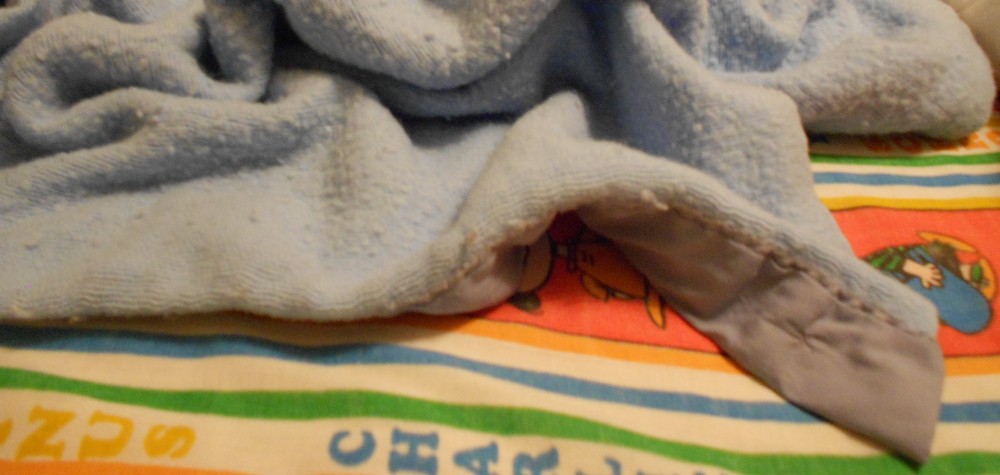

The need to take him out of his cage, or rather the need to keep him in a cage, or perhaps, the whole situation of pets in cages, had become increasingly troubling for me in the past few years. Part of my growing discomfort had to do with seeing Smeagol, essentially a wild animal who had grown to about four feet long, confined to a glass box, where he seemed to spend a good amount of his time searching for a way to get out. Snakes, as a rule, are pretty darn good at finding ways of getting in or out of wherever they want. So I imagine being trapped in such a way was maddening for him.

Part of my growing discomfort had to do with having dogs who have fairly free rein to go anywhere they want within the house and backyard—something I marvel at from time to time in the sense of, “Wow! We have some fairly large animals just wandering around our house.”

When I was very young, we had a dog that was on the scene before I was, and who didn’t have much use for me, and vice versa. I never marvelled at her, and rarely even realized she was around. Seriously, I can barely recall her existence, aside from some vague memories of my siblings’ reactions from around the time she was put down. I also didn’t give much thought to the idea of keeping animals confined to cages. In junior high and high school, well after the dog was gone, I acquired quite a few reptiles and amphibians (no snakes), and occasionally rodents, that were kept in a variety of fish tanks, mostly in my bedroom. Hell, once, with the help of my younger brother and a friend, I even transplanted a (slightly-larger-than-puddle-size) pond’s worth of native Oregon frogs (tiny little creatures) from their home in the suburban wild to a tank in our backyard—never thinking about just how difficult it would be to sustain that little ecosystem as the summer wore on and the heat became unbearable in that glass box. They were tadpoles when we caught them, and monitoring their transformation to frogs was pretty amazing. But we could have just visited the pond repeatedly and gotten the same basic show, all without wiping out the small frog community.

The vast majority of the reptiles and amphibians I collected met with premature deaths, often for reasons unknown, but more often through my own failings. There was a red-eared slider (turtle) who died shortly after I fed him bologna, unaware that turtles cannot physically process fat in their food.

There was the fire-bellied newt who escaped his cage (how a newt climbed out of a fish tank with only a few inches of water in the bottom, and a few flat rocks and a small branch poking out of the water is beyond me). I found the newt several days after his disappearance when I stepped on his dehydrated, crunchy little body, tangled in the shag carpet downstairs by the front window. I can only imagine the adventure he had making his way down the steps.

There was a procession of anoles (small lizards they sell in pet stores as chameleons), one to three at a time, who all caught the same wasting disease, despite thorough cleanings of the cage between inhabitants.

Various other turtles and lizards succumbed to death prematurely, with no real indication that anything was wrong until they woke up dead.

Later, well before my daughter acquired Smeagol, she had a pair of Russian dwarf hamsters—one of which completely consumed the other, except for its pelt. I kid you not. There were no bones left or anything else aside from a well-preserved fur, in the style of a stripped and cleaned item you would find at an actual furriers. What was left of the devoured hamster would have made an excellent rug for, say, a beetle’s bachelor pad. I’m not sure if the consumed hamster died of natural causes before it was cannibalized, or if the carnivorous hamster just decided he’d had enough of corn and seeds, or maybe had had enough of her roommate’s bad habits.

But enough with the tales of animal woe. At this point, I’m going to make a little pledge in honor of our too-soon-taken Smeagol. I’m done with pets that have to be kept in cages. I don’t want to contribute anymore to the kind of recklessness that involves people boxing up animals in the first place. This is not to say that I think it is inherently wrong to have pets that are kept in cages. I suppose in some cases, it makes life more pleasant and less dodgy for the animals, and hopefully involves children learning some measure of responsibility, and hopefully a great deal of kindness and love. But in my personal weighing of the situation, I’ve made too many dumb mistakes. And I’ve failed to provide adequate levels of life outside the box. I’ve apparently failed to monitor properly for signs of illness, and to make sure I was avoiding harm.

Smeagol deserved a greater measure of freedom than he got. Of course, a ball python could do worse in life than to have a safe, warm home with regular feedings. But a snake native to the East coast of Africa probably could have done much better than to be kept in a glass box in the Northwest corner of the U.S., cared for by someone with a large measure of phobia aimed at him.

So, peace to you, Smeagol. May you pass through the fires of Mordor to the place of white shores and beyond—a far green country, under a swift sunrise.